A Bit of Dye History

Since antiquity, in all civilizations across the globe, man has practised the art of dyeing cloth before acquiring the skill to write. Dyes are symbolic of their era and owner; each different culture evolving their own usage of local plants and dyestuffs to make colour and dye their clothes, often linking dye to ritual, using colour to identify and communicate ones belonging to a specific social class or tribe. Dyes were used for protection, to achieve victory in war, but mostly dyes were an expression of beauty or rank.

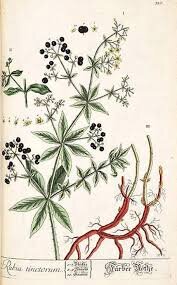

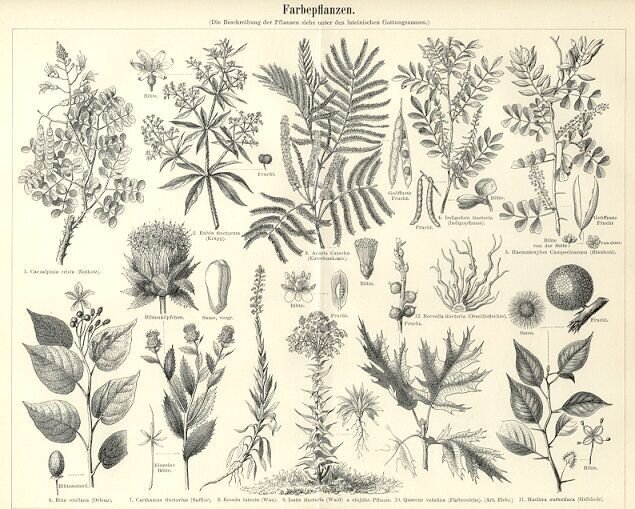

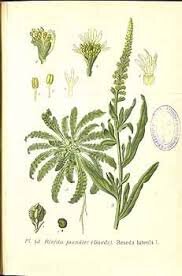

In prehistory man used a lot of mineral dyes: ochres, yellows, greys and black from charcoal, but quickly began to derive colour from plants: berries such as the sambucus nigra, yellows from broom and blue from woad. Evidence of a wide range of materials used can be found amidst the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. We know that dyeing contributed significantly to the Roman economy with emissaries sent to collect recipes and processes from across the Empire and dyes such as the famous purple from the Bolinus brandaris reserved only for imperial usage. A Collegium tinctorium was formed on the basis of the colour they specialised in.

We practised botanical colouring for millenia, exchanging dyestuffs along trade routes from India through Turkey and the Orient.

The middle Ages saw the development of the first dye factories with dyeing corporations emerging alongside the first texts for recipes. By the 10th century the art of dyeing had flourished throughout Europe, and Venice began to emerge as a place of exchange for the dye trade and the art of coloration. In 1540, a wonderful text was published by Giovaventura Rosetti containing over 200 dye recipes, with observations anticipating modern dye chemistry.

Intense textile manufacturing increased in Italy with expansion of the naval trade and since the 16th century, vast exchanges of logwood, madder and indigo increased across the Atlantic and through Persia to deepen and enhance our European palettes. During this period, some dyestuffs became valued more than gold. Dyers who mastered their art with refinement caught the eyes of kings and were sought after by the European courts. Vast plantations of woad and sumac were born serving the bourbon palaces and many villages emerged as dye centres.

However, since the industrial revolution and the invention of mauveine in 1856, petrochemical dyes have steadily ruled the market. Today, petrochemical colours are supreme, only 1% of textiles are dyed naturally, with only rare indigenous pockets of knowledge remaining and botanical dyeing lying principally in the realm of conservation , restoration and textile art.

Tomorrow however, botanical dyes could be salvaged from history and brought into a post-petrochemical future.

We can produce dye extracts now from biodynamic agriculture as well as pigment from food waste. Carbon farming dye plants harvests carbon in the atmosphere through photosynthesis and fixes it into the soil. We have seen many recent demonstrations of people regenerating the cultivation of dyestuffs, not only organically but in sustainably restorative ways. Increased experiments have proven there is a strong case for repositioning natural, botanical dyes within a greener, more sustainable textile market. Thanks to many scientific studies, we understand the phytochemistry of dyes more than ever before, in order to guarantee colour consistency and fastness.

It is time for a complete behavioural shift within our industry, looking at how to rebuild a value chain for the 21rst century.

By coming together within this hub, we hope you will upload and exchange narrative, knowledge, exchange recipes, upload colours, expand our palette…Please get in contact, discuss solutions, discuss new mordants, exchange methods, organise workshops and dye…differently.

This hub is a participative, sharing platform, based on creative commons; it will evolve as we all add our work to it.

It is a hub for colour enthusiasts aimed at those who make and work with colour at many different levels, please feel welcome to join and collaborate below.

-Author: Jackie Andrews-Udall

THE HARSH REALITY OF PETRO-CHEMICAL DYES

“Many of the chemicals used in textile production are known to have adverse health and environmental impacts...Many dyes contain heavy metals, such as lead, cadmium, mercury and chromium (VI), known to be highly toxic due to their irreversible bioaccumulative effects, whilst azo dyes contain carcinogenic amines”

— UNEP REPORT: Greenpeace 2018

“The textile industry is notorious for its impact on water systems. Despite this notoriety, surprisingly little data exists on the scale of water pollution from textile processing, and the often cited claim that 20% of industrial water pollution is attributable to the dyeing and treatment of textiles is unsubstantiated”

— UNEP REPORT